International arbitration in 2021

Investment arbitration trends

Which sectors and events do we expect to give rise to new claims in 2021?

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented government intervention over the last year. Although there have been limited challenges against States under bilateral or multilateral investment treaties to date, we expect that further claims are likely to emerge over the coming year. Other contexts in which claims could arise this year include recent energy sector reforms, but also measures concerning less traditional forms of investments, such as those regarding new technologies and the banking and finance sector, particularly in the pension fund business.

Government measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic

In order to cope with the effects of the pandemic, governments around the world have taken a wide range of measures that have affected all sectors of the economy. Foreign investors and their investments have not remained immune. In some instances, well-intended government measures have disproportionately affected foreign investments.

For example, as we discuss below, numerous countries have reformed, or are considering reforming, their pension fund regulations to allow participants to make early withdrawals, which will have a significant impact on the financial health of the funds, most of which are owned by foreign financial institutions.

A question in most COVID-19-related investment claims is likely to be whether governments, in parallel to the restrictions allegedly necessary to combat the spread of the pandemic, should have also adopted reasonable mitigatory measures or even rescue plans to ease or share the harm suffered by investors. Another question will be whether governments have used the pandemic as an excuse to further their political agendas unrelated to the health crises, at the expense of investors’ acquired rights. Alleging that renewable energy generation poses a safety risk to the national grid in a context of reduced electricity demand owing to the pandemic, the Mexican government has taken measures to delay or prevent renewable energy projects from coming online, deliberately benefiting State-owned energy companies.

The crisis is far from over, and how deep the economic impact will be is still unclear.

Pension funds

Investment arbitration is becoming increasingly popular among banks and financial institutions. In the last few years, claims have been filed in relation to the forced conversion of the currency of loans, as well as State bailouts and compulsory administration of banks in the midst of the financial crisis.

To add to these, in the next few months investment treaty claims may also arise from regulatory changes in the pension fund sector, particularly in Latin America. Arbitration proceedings have already been commenced by fund managers, so-called pension fund administrators or AFPs, against Argentina and Bolivia, due to the migration of the pension system back to public administration. In Chile, a similar initiative will be the object of a constitutional amendment to be debated in the course of this year. The role and remuneration of private pension funds is also under review in Mexico, Uruguay, Peru and Colombia. These proposals may gain support as States seek to tap resources from the pension system to finance COVID-19 recovery policies. The COVID-19 crisis has also led States to allow contributors to withdraw extraordinarily a certain amount of funds from their pension schemes, thus causing fund managers to incur unexpected operational costs to satisfy demands.

Energy

Recent times have witnessed policy reforms and legal changes in the energy sector in several countries. Modifications often amount to a retreat from previous programmes to incentivise private investment and increase energy efficiency, reduce carbon footprints and meet emissions targets. Through administrative, legislative and even court actions, programmes that typically included privatisations, promises of long-term legal stability and financial incentives, such as ‘feed-in’ electricity tariffs, are being abandoned or profoundly altered.

- In Mexico, for example, legislative changes in the electricity framework range from cuts in the income incentives for renewable energy projects, to the suspension of operation tests for new plants and to the alteration of dispatch rules, all apparently designed to favour the State-owned electricity company. In Peru, a supreme court decision has prompted proposals for a potentially adverse reform of dispatch rules for thermoelectric generators.

- In Chile, the government is planning to phase out completely all coal-based power plants by 2025

- In Argentina, after years of tariff freezes in the gas and electricity sectors, the government has now forced a new renegotiation of remuneration regimes

- The Ukraine government has significantly reduced the feed-in tariffs it had originally offered investors in the renewable energy A similar measure was adopted by the French parliament at the end of last year.

Measures such as these may give rise to a wave of international claims by foreign investors pursuant to investment protection treaties. It would not be the first time that sudden regulatory changes end up like this. The claims sparked by the Argentine emergency measures in 2002, and the more recent renewable energy cases against Spain, Italy and the Czech Republic, are the prime examples of what may come.

Technology

2020 has underscored the importance of the technology sector. It has proven crucial in remote working and in keeping the global economy going during the COVID-19 pandemic. With this increased focus on technology, investment in this sector is also likely to be greater than ever. At the same time, there are indications of mounting government intervention for security, tax and consumer protection reasons, given the absence, in many jurisdictions, of specific regulatory frameworks for new technology. For example, in Asia, China’s new Export Control Law, which came into effect in December 2020, imposes certain export restrictions on sensitive technologies. A number of countries in Europe, including the UK, France, Spain and Italy, are seeking to collect a digital services tax from technology companies. In Australia, the government has been investigating competition and consumer protection issues in relation to digital platforms, such as Facebook and Google, which is likely to result in a regulatory intervention.

With more government involvement, the technology sector is likely to become more sensitive to State action and inaction, which, in turn, is bound to give rise to investor-State disputes. So far, technology companies have not resorted to investment arbitration in resolving such disputes as frequently as companies in other sectors. However, such arbitrations are on the rise. Reportedly, the Canadian taxi tech company Espiritu Santo has commenced arbitration proceedings against Mexico; and Uber has put Colombia on notice of a possible arbitration, following the government’s ban of the use of the car-sharing app.

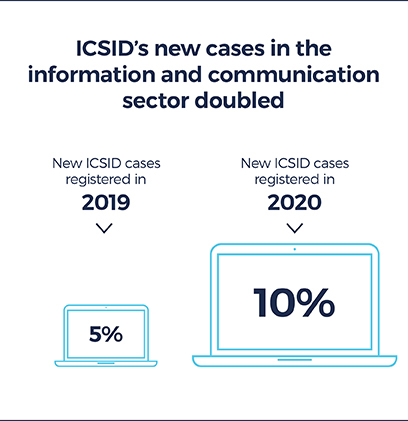

ICSID’s case statistics demonstrate a rise in investment arbitrations in the technology sector from 2019 to 2020. This trend is likely to continue in 2021.

International arbitration in 2021

- Introduction

- The future of remote hearings in a post-pandemic world

- COVID-19-related disputes: trends and predictions

- Insolvency and arbitration

- Arbitration in the EU and UK: a changing landscape

- The future of investor-State dispute settlement

- Investment arbitration trends

- Investment claims: project finance lenders have rights too

- Latest arbitral rules reforms

- Continuing economic woes for the construction and infrastructure sectors

- Arbitrators’ duties of disclosure in the spotlight

- Arbitration and climate change